Alumni interviews: Ellen Söderhult

In connection with SKH's tenth anniversary, we wanted to ask some alumni how they experienced their time at the university. Those we have interviewed studied at the time when we still used the names University College of Opera (OHS), Stockholm Academy of Dramatic Arts (SADA) and DOCH School of Dance and Circus alongside SKH. Now it's time for Ellen Söderhult, who studied the bachelor's programme in Circus at DOCH from 2007 to 2010 and the bachelor's programme in Dance at DOCH from 2012 to 2015.

Tell us a bit about your background and how you came to choose DOCH for your education.

– I have attended two programmes at DOCH, the first was in Circus, the second in Dance. The preparatory programme I attended before DOCH visited the Circus Hall in Alby and that experience grabbed me in different ways. Once I was in the circus programme, I practised dance outside of school with a person who was in the dance programme and became very interested in it. Then my interest shifted completely to dance, and Sindri Runudde, who also came from circus, and I applied together.

In secondary school I studied nature with a specialisation in choir so the first time I applied for higher education I chose between DOCH and the medical programme, but the second time it was, so to speak, a bit more fine-tuned navigation!

I got into circus because my teenage best friend read about a circus course for beginners in the back of a magazine and signed us up for it. I don't think I even knew there was such a thing as contemporary circus or contemporary dance at the time, but it didn't take long for me to develop a passion and become obsessed, both with the art forms and with performing them.

How did you experience your time at the university?

– The two programmes were completely different. My time in Alby was extra physical and I was very concerned with getting stronger and with passing different difficult elements. My three years on the dance programme I think had a bit more to do with understanding the art form of dance and what appealed to me about it. Through practising, experiencing works and reading, I came to understand more about how I wanted to live and express myself through it.

Were you affected by the merger of the three schools into SKH?

– Yes, because I was a student representative on the University Board when the merger began. I also sat on a temporary student council with student representatives from what was then SADA and the University College of Opera. Anna Lindal [former professor at SKH and member of the organisational committee that worked during the merger] was also very involved. I remember it was very nice to talk to the representatives from the other schools and to Anna. Perhaps it was because Anna had so much experience of both something completely classical and something brave and experimental, and because it was fun to hear about what the other students were looking for in the merger. I feel like the whole Bologna thing had already made a lot of people within arts education worry about their craft skills and that there would be more standardisation between programmes that had completely different goals and content.

What did you do immediately after your degree and what are you doing today?

– I create choreographic works and work as a dancer. I have been doing it all the time except when there was covid, then I went to a music folk high school for a while.

Was attending a school with many different artistic specialisations an advantage for your future professional network?

– No, it hasn't been yet, but of course it could be!

– How do you see SKH today?

I look at SKH with hope that it will be an institution that can make a powerful difference in working against the strong whiteness norm in what is seen as the history of the art form and in scrutinising the institutional racism that exists in Sweden.

We are in a situation today where there are, unfortunately, major shortcomings in cultural policy that are affecting arts education. A large majority of applicants have parents with an academic education, which is a democratic problem, as an important aspect of having state-run education is to make the art form and its practice accessible to more people. It is therefore important that the profession is viable and that the institution does not use its power to police accepted concepts of quality or standards.

I believe that the institution has a position of power, partly by determining who gets in, that is, what bodies, experiences, interests and inclinations the admitted have, but also and even more so how the institutions relate to heritage and, for example, in the case of art education, a white, Eurocentric view of art and art history.

Because the economic conditions in the field are so harsh now, it is also not as inviting and accessible as it should be to practise non-institutional art. It is a major problem that it is almost impossible to make a living as a dancer in the independent field and this limits who enters and stays in the profession.

I also hope and believe that SKH will hold the flag high for critical thinking, for the value of art and free cultural life, and that art should not only be for the privileged.

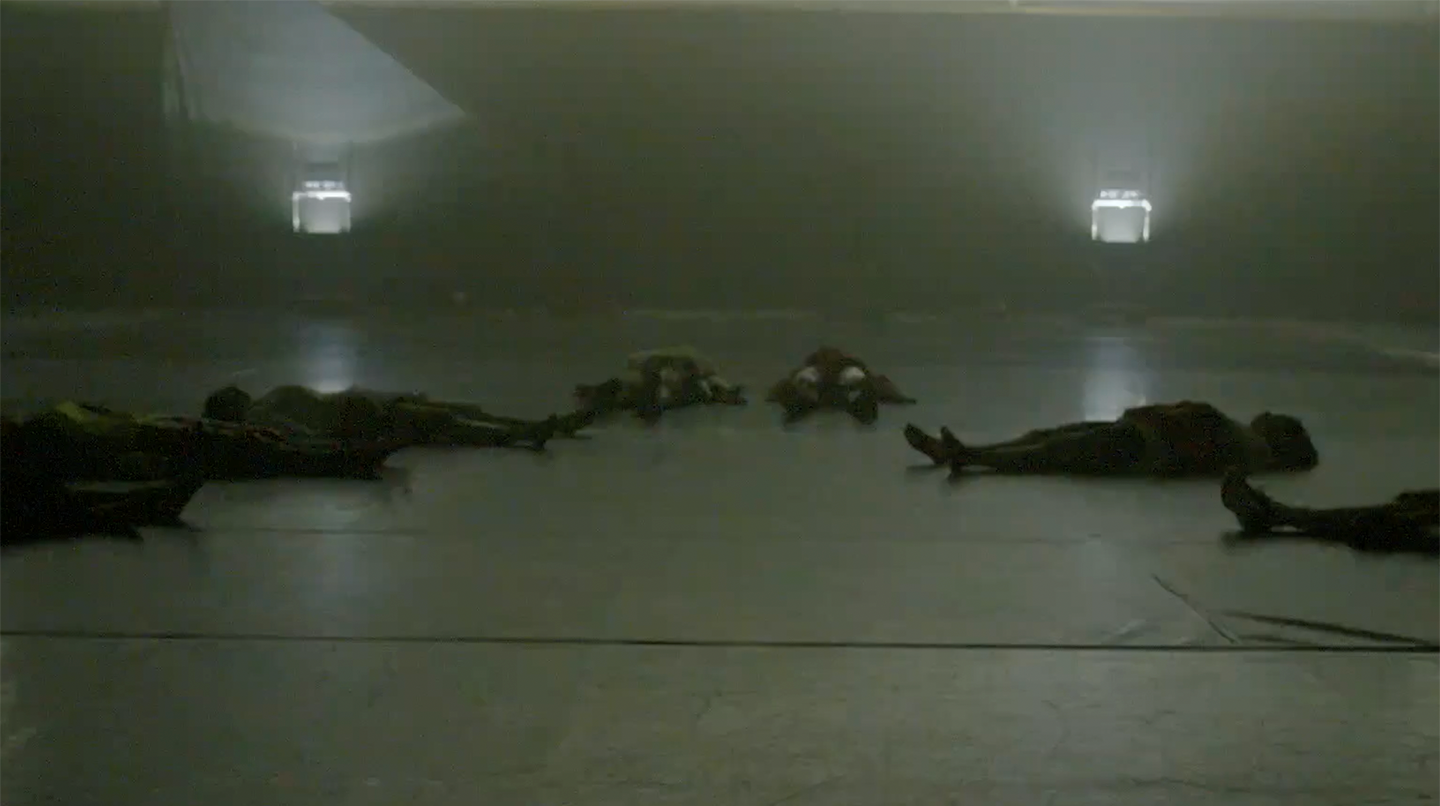

Mover's Signum, Dansens hus/Elverket, still from video documentation (artistic director: Thomas Zamolo)

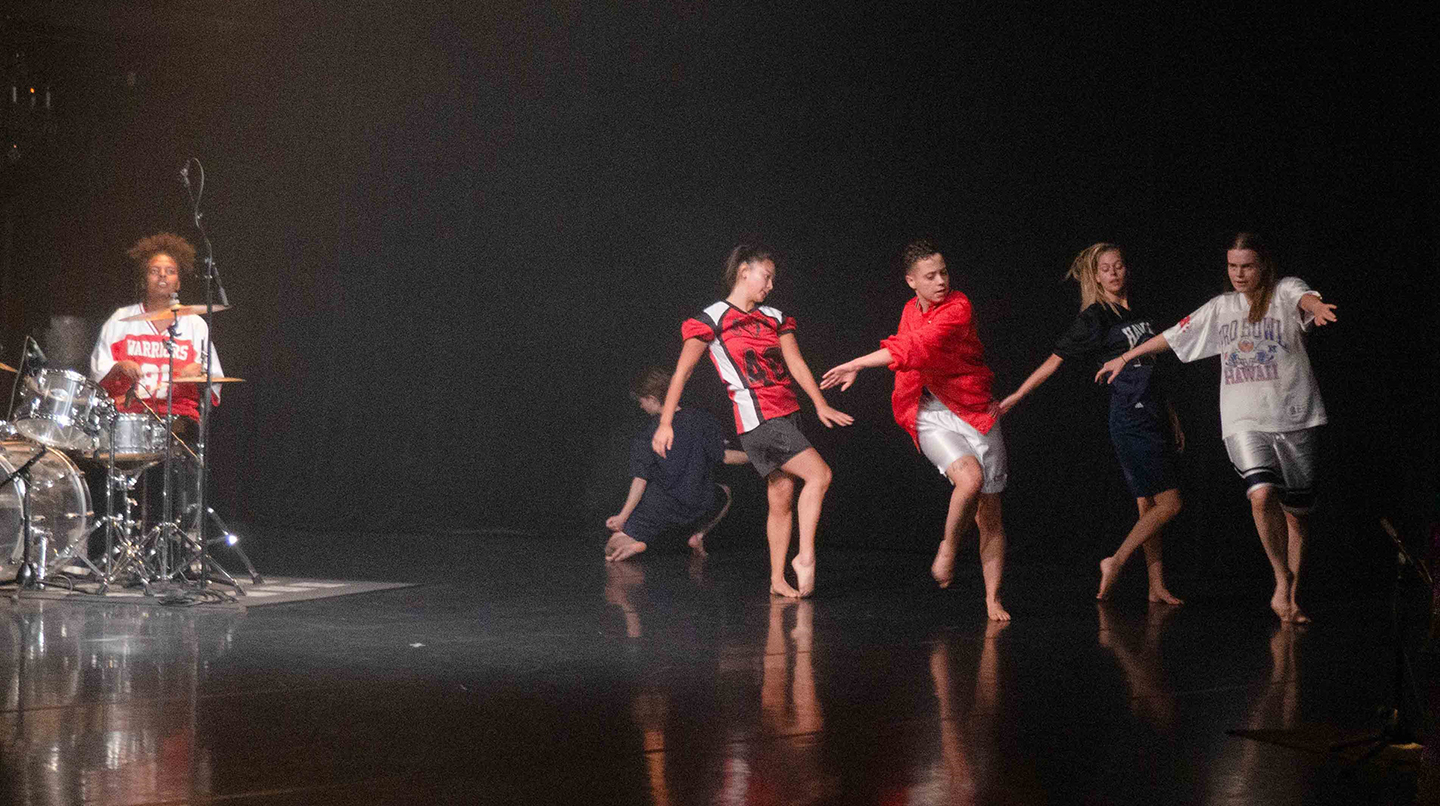

GROV (2023), still from video documentation by Karl-Oskar Gustafsson

How to do things with Romance (2021) at Dansstationen (photo: Olle Ehn Hillberg)

SKH 10 years

SKH is celebrating ten years as a university college in 2024, ad we'll be filling the year with retrospection, foresight, articles and events that connect to the decennial in various ways.

Ellen Söderhult (photo: Ingrid Söderhult)